Today I was going to go to Tian’anmen Square, not because there’s anything there I particularly wanted to look at, but because it’s huge, hugely symbolic and a place where you can still witness the forces of authoritarianism at work. It’s where you are most likely to find triumphant statues celebrating Mao and the revolution, and although you’ll find Starbucks and KFC at the very fringes of the square, it’s one of the few places left that don’t seem to have succumbed to the ugly trappings of Western consumerism that have engulfed most of Beijing. I thought a bit of retro communist propaganda might be fun.

The square is absolutely huge – it will hold a million people easily – but I never got in. Imagine saying that of Trafalgar Square, a miniscule fraction of the size. “I got there, but I couldn’t get in.”

I took the subway to its southern end, left the station, followed signs down into another underground passage and up again, a pointless diversion if there was ever one, and followed yet another sign that led me to a security barrier. I had walked several hundred meters but travelled a handful.

They have security barriers everywhere in Beijing. You have to scan your bags to enter any subway station. I’m not sure what the exact threat is, aside from those pesky democrats, but on the subway trains the police run strange cartoons, animated a la South Park, warning of dark forces at work. Apparently, bad men, usually blond and tattooed, will drive around shooting you if you fail to be vigilant. I think. Either that or it’s a Chinese knock-off of Team America.

At the square, I approached the barrier. A small official barred my way and indicated that I had to join the back of a Chinese guided tour party, even though I wasn’t part of the tour. The party filtered through in front of me, but when I got to the front, the same official barred the way again, putting his hand on my chest. He snapped something at me in Chinese. I said I didn’t understand. He pointed into the distance and said, sharply, “one hundred meter!” So I said “oh fuck off, you can keep your stupid square” and loped off, muttering darkly to myself; an incident no doubt recorded by one of the zillion CCTV cameras that watch the area.

It was while I was muttering that I noticed the Beijing Railway Museum. I’d seen it listed on a map, but noticed that it wasn’t mentioned at all in my Lonely Planet Guide. This could mean only one thing: it was a crap museum.

Now I rather like a crap museum. There’s something endearing about wandering around a place that someone passionately believes should exist, but which in fact appeals only to a very, very small number of people. Local history museums are the perfect example, especially the ones with a volunteer or two dressed up in period costume, using biros sellotaped to feathers as a “quill pens” and sporting comfy sneakers with their pilgrim garb. They never have enough money in the cash box to make change and the exhibition highlight is a display case of rocks. I’ve been to crap museums all over the globe. The last one I went to, in Milwaukee, was so crap that the young student who was on the desk waived me in without charge, such was her surprise at seeing anyone at all. I was the only visitor. All day, probably. But I love being the only person in a museum, just as long as no-one bothers me while I’m there by asking me where I’m from and would I like to become a Friend of the crap museum.

Railway museums are usually very popular, especially if there are lots of working trains to clamber over and stout, beardy men with a far-off look in their eyes in the neighbourhood. I had a hunch this museum wouldn’t be one of them. I’m not sure if train enthusiasm is even a thing over here. Beards certainly aren’t. And I was right. It was almost empty, probably due to the fact that it is a railway museum as opposed to a train museum. There really aren’t any trains at all, just lots of displays about railway lines. And points. And signalling.

It was kind-of perfect, the displays so mind-numbingly dull that I could have a good giggle and almost forgive the officious little prick of a policeman in the square outside.

There was a captivating display of railway sleepers throughout history. That was next to another that showed the evolution of the things that clamp the rails to the sleepers. And don’t get me started on the rails themselves or I’ll be here all day.

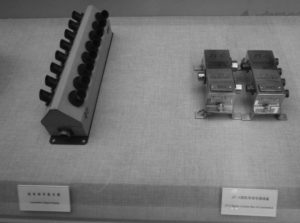

This cabinet showed me a locomotive signal display and a signal junction box. I’m so glad I didn’t miss those:

And here, on several square meters of red velvet, are the scissors that were used by Hu Jintao to open a railway line:

The museum, packed with visitors (don’t be fooled by the closed-to-visitors mock-up of a bullet train in the distance):

The basement was given over to large model landscapes of railway lines, impressive in their way but largely meaningless to me. When I approached the model of a Tibetan branch system, one of the museum attendants (of which there were many, all bored off their tits) nipped over to throw on a switch to illuminate in red the most important line in the model. It was the moment to deliver my payback for the Tian’anmen Square Incident, so I looked at it for about five seconds before walking purposefully away, hoping to convey that I wasn’t much impressed.

People’s Republic of China, 1 – Gillett, 1.

Moments later, I exited through a dusty gift shop. All I can tell you about Chinese railways is that they built a lot of them and continue to do so. Oh, and the first Chinese train was a knock-off and it was called The Rocket.

Some things never change.